Simon Armitage (Professor of Poetry): Bowie

I was excited to hear that Dr Denis Flannery is running a course called Bowie, Reading, Writing at the University of Leeds. As a student it would have been the kind of module I would have signed up for without hesitation, though the academic study of pop/rock music was generally frowned on back in the early eighties, added to which I was a Geography undergraduate, so it was never going to happen. When Bowie died I was approached by two or three newspapers and magazines to write about him. Either I couldn’t or I wouldn’t, but either way, I didn’t. Then more recently, I did, and I offer them here as two ways of approaching the same subject, more or less. The first is a ‘prose poem’, composed for the Yorkshire Sculpture Park to mark their 40th birthday and published in the collection Flit, in which I imagine the Park as a small mid-European enclave where I am living in self-imposed exile. There’s a Brexit theme somewhere in the background. I could never have imagined that a piece about Bowie would have developed out of such a project, but commissions often lead to unanticipated outcomes, which is part of their attraction. There’s no such thing as a ‘prose poem’, of course, despite the industry and commentaries that have grown up around the idea. You’re either working with line-endings or you’re not (i.e. you’re either ritualising language through the deliberate manipulation of line-breaks, or you’ve handed those responsibilities over to the geometrical preoccupations of a typesetter). But I’ve written one anyway, because to be born is to be a hypocrite. The second piece was written for the New Statesman. The brief: “The night that changed my life.” Of the several writers to contribute to the article, it was interesting how many of them wrote about musical experiences, and how few of them about literature or books. To go back to my prose poem point, if the first piece is, why isn’t the second?

A New Career in a New Town

David Bowie called. Before I could get into the specifics of him being dead and this being a private, unlisted number, he said, ‘That’s a foreign ring-tone, man – are you abroad? Always had you pegged as a bit of a stop-at-home, curled up in your Yorkshire foxhole.’ I told him I was in Ysp, flirting with communism, alienation and Class A narcotics, and working on my experimental Ysp trilogy. He said, ‘Simon, your imagination is telling lies in the witness box of your heart. But listen, will you write the lyrics for my next album?’ ‘Why not,’ I replied, and quickly we thrashed out a plan of action. It would all be done by electronic communication – no personal contact, no face-to-face meetings. David laid down some backing tracks and over the next year or so I worked up a suite of songs – verse-chorus stuff, nothing too pretentious or avant-garde. ‘These are genius, man. You could have been a poet!’ he said, laughing like a cheeky cockney in the saloon bar of a south London boozer circa 1969, his voice like cigarette smoke blowing through a pre-loved clarinet. ‘One thing I always wanted to tell you, David,’ I said. ‘When I was about thirteen I was really into table tennis but had no one to play with. It was just me versus the living room wall, on the dining room table. One night I went down to the local youth club, where all the roughnecks used to hang around, and made my way to the top floor where the roughnecks were playing table tennis, lads who’d stolen cars and thrown punches at officers of the law. I was wearing shorts and sweatbands in the style of my favourite Scandinavian table tennis champion of the era whose deceptive looping serve I hoped one day to emulate and whose life I wanted to live. I felt like a kid goat pushed into the tiger enclosure at feeding time, but they ignored me, those roughnecks with their borstal-spot tattoos and broken teeth, just carried on playing, the small hard electron of the ball pinging back and forth across the net like the white dot in that seventies video game.’ ‘Pong,’ said David. ‘Exactly,’ I said, ‘Just carried on smoking and swearing and hammering the ball to and fro under the yellow thatch of the canopied light in the darkened upstairs room. And here’s the thing: every time he hit a winner, the roughest of those roughnecks would sing a line from Sound and Vision. “Blue, blue, electric blue, that’s the colour of my room,” he’d croon as he crashed a forehand to the far corner of the table, or “Pale blinds drawn all day,” when he flipped a cheeky backhand top-spinner past his bamboozled opponent. You probably scribbled those words on a coaster in a Berlin cocktail bar or doodled them with eye-liner pencil on a groupie’s buttock, but they’d carried all the way to a dingy youth club in a disused mill under a soggy moor, into the mouth of one of those roughnecks, who’s probably dead now or serving life.’ David sounded pensive on the other end of the phone, perhaps even a little tearful. ‘I have to go now,’ he said. I could hear the technician checking his seatbelt and oxygen line for the last time, touching up his mascara, lowering his visor. Then the engines started to blast and the countdown began. I wandered down to the big Henry Moore in the park and lay on my back in the crook of its cold bronze curve, watching the skies, waiting for the crematorium of night to open its vast doors and the congregation of stars to take their places and the ceremony to begin.

*

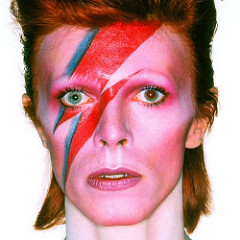

In 2013 my wife took me to the David Bowie Is exhibition (rubbish title) at the V&A for my birthday. I’m a bit grumpy about exhibitions. I don’t like organised tourism or being herded along. I hate queuing. Also, the V&A is all about medieval needlework and classical statuary isn’t it - what would they do with Bowie apart from categorise and sanitise and ossify him and flog me an Ashes to Ashes pillow case or Aladdin Sane teapot and shove some of his spangly leotards in a glass case? The first few rooms were mostly costumes and were full of people reading captions and programmes out loud to themselves, so I broke rank and went ahead to the “lyrics” section. The poet in me was determined to be more interested in words than platform shoes etc, and I lingered over the schoolboy handwriting and clumsy typewriting, spotting lines that had been drifting through my mind and floating around my bloodstream for decades. Wandering deeper into the maze of rooms and corridors, mostly on my own now or perhaps just not noticing anyone else, I began to feel as if I was falling into a David Bowie themed kaleidoscope, cover art and iconic photographs and pop videos reflecting and refracting from every surface, the experience intensifying and the momentum quickening, everything leading towards the source of the light, to Ziggy Stardust. Not Bowie’s first album but the first album I bought, around which I’ve constructed all kinds of personal fantasies and creation myths. But at the core of those fables is solid truth, a truth that stuck me forcibly as I reached the finale of the exhibition. As a bewildered teenager floundering in 1970’s semi-rural post-industrial northern England, Bowie was my secret Jesus. There was another way of being in this world, and that weirdo spaceman creature with the whiny voice and see-through skin was alternativism incarnate. In the vast hall at the end of the tour, concert footage was playing on enormous screens on all four walls - it was hard to know which way to look and where to listen. Eventually one screen remained lit, floor to ceiling, the ‘Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars’ tour, Ziggy announcing his imminent self-assassination, Bowie sing-talking the first verse of ‘Rock ‘N’ Roll Suicide’. Fair play to the esteemed and decorous V&A, it was ******* LOUD; when the bass drum kicked in I could feel it pulsing in my rib cage. And when Bowie pleaded those final lines: “Give me your hands - you’re wonderful” over and over, I was a fifty-year-old poet and a fifteen-year-old nobody with tears streaming down his face, reaching out with everyone else in the crowd to touch the untouchable.

Simon Armitage